© 2024 First Samuel Limited

Investment evolution

Arguably one of the most significant evolutions in the world of investment markets over the last 50 years has been the growing prevalence of exchange traded funds (ETFs).

ETFs are a financial technology that was catalysed by the emergence of index investing in the early 1990s, which brought accessibility of investing to the wider general public. My colleague, Paul Grace, recently wrote more about index investing (or ‘track-the-market investing’) here.

What are ETFs?

ETFs are managed (or ‘pooled’) investment funds that are listed on a stock exchange. Buying and selling a listed managed fund is as easy as buying or selling a normal share. The usual form-filling in that accompanies an investment in a managed fund is done away with.

ETFs are generally characterised by low fees and accessibility to diverse investment strategies.

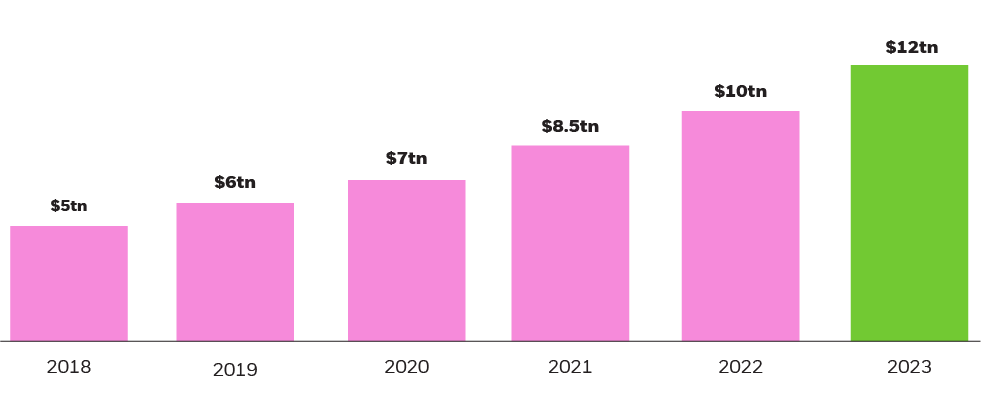

Success

The stunning success of ETFs can be measured by the growth in assets under management (AUM) – eclipsing $10 trillion globally in late 2021.

In Australia, the ETF landscape is dominated by three large issuers in particular: Vanguard (28% market share by AUM), iShares (19%) and BetaShares (16%), which together had around $140 billion in assets under management at 31 December 2021, a staggering 123% cumulative growth in AUM over the previous two years (source: BlackRock).

As the ETF market has matured, so too has the breadth of products offered by ETF issuers. This universe now encompasses:

- Index tracking (passive), actively managed and even long/short strategies

- Specific geographical- and sector-tracking strategies

- Thematic ETFs, which attempt to capture market trends (such as renewable energy or ESG, to name examples)

- Non-equity asset classes, including bonds, commodities and currencies.

Beware

There is no doubt that ETFs will continue to grow, generally benefitting investors through providing low-cost diversification and accessibility to investment markets they could not otherwise access efficiently. However, there are some considerations to be aware of.

1. Cashflow considerations

The ATO allows ETF trustees to attribute income to investors rather than paying income immediately via trust distributions (as in the case of traditional trusts). This allows ETFs to defer the payment of income from underlying investments until defined distribution points.

Additionally, it is not always necessary to physically pay-out the distribution, rather it can be “paid” through issuing additional units in the ETF under a distribution re-investment plan (DRP).

Investors therefore need to consider their own cash flow requirements ahead of any decisions to invest in ETFs, including how much portfolio weight to ascribe to them and the impact of participating in any DRP programs.

2. Tax treatment of ETF structures

ETFs are required to issue ‘AMMA’ (attribution managed member annual) statements to investors. These detail the various tax components of ETF distributions paid to investors (commonly quarterly), which must be disclosed on individual tax returns.

These components can be numerous, complex and confusing, and may include amounts of net income, franked and unfranked dividends, franking credits, foreign and domestic sourced income, realised capital gains and others. Investors will also need to calculate the realised capital gain or loss made on ETF trades, which can be made more complex as the tax cost bases can be impacted by the components disclosed on AMMA statements!

Correct tax reporting by individual investors in ETFs is an administrative burden that is really the domain of a tax accountant and necessitates the keeping of detailed records by ETF investors. Investing in ETFs via a managed investment service (including First Samuel) or platform can alleviate a lot of this complexity.

3. Management by ETF managers

ETF issuers typically purport to be efficient in the way they internally manage the basket of investments that comprise the ETF. This assertion is not without nuance, and is not necessarily shared by the ATO and other financial market participants.

- Capital Gains/Losses: It is true that index-tracking ETFs generally have reduced turnover of securities, and therefore reduced triggering of capital gain tax events. This is because trading activity is minimised to the extent necessary to track the index benchmark. Tax on capital gains is not paid within the ETF but instead passed through to the investor (via a distribution of net capital gains, as discussed earlier) with tax paid in their hands.

ETF managers also attest to optimising ‘discounted capital gains’ (i.e. accessing the 50% discount for holding securities more than 12 months). However, as the mandate of ETFs is to track an index or other non-tax benchmark, they are usually unable or limited in specifically managing for CGT outcomes – the priority goes to tracking the index or benchmark ahead of the tax optimisation (even where it would provide a worse outcome).

- Franking credits: Exposure to franked dividends (and associated franking credits) in ETFs again hinges on the underlying objective of the ETF, which generally is not related to tax outcomes (though some ETFs have a specific objective of generating higher franked dividend yields, which involves unique risks). Investors in ETFs receive the attributed franked dividends/credits via periodic distributions.

To summarise, tax outcomes in ETFs are managed at the fund level and are secondary to the primary mandate/objective of the ETF. As consideration is only made at the fund level, any unique tax considerations of individual investors are not considered by ETF managers.

- Lack of control over pooled assets: Individual investors do not have the ability to have the management of the ETF tailored to their individuals needs. At law, the management of the ETF must be run for all investors.

This is best illustrated by describing a rarely acknowledged and clearly misunderstood phenomenon which occurs with the treatment of capital gains within ETFs, due to individual investors buying and selling ETFs. That is, each and every ETF investor pays capital gains tax based on the trading actions of others.

Consider this hypothetical example.

| John purchased 1,000 BHP shares and retained them indefinitely (for simplicity – assume no corporate activity that gives rise to a CGT event that is out of John’s control). John will pay NO capital gains tax ever, so long as he does not sell the shares. In contrast, John purchases 1,000 units in OzMiner ETF which tracks the performance of BHP shares, and retains them indefinitely. Another investor in this ETF sells their holding, reducing the assets under the management of the ETF. This causes the ETF manager to sell BHP shares to reflect the new level of assets under management. This triggers a capital gain which is distributed to ALL investors in OzMiner ETF, including John, on which he must pay tax. Here, we have the perverse and unintended situation where John is required to pay tax on capital gains attributed to him, yet he has not sold his ETF holding. He must pay tax for the trading activity of other ETF investors! |

Avoiding the traps: the MDA difference

In contrast, a managed discretionary account (MDA) provider like First Samuel, is able to manage individual outcomes at the account level. This means we can incorporate specific client considerations, including their own tax situation, into the way we manage each individual portfolio.

Generally, we prefer the control and flexibility that direct investment in securities provides (relative to ETF investment), unless additional benefit can be derived. Whilst we may also use ETFs from time to time, their inclusion and weighting is generally limited and only in consideration of the specifics of the individual investor.

As always, we invite you to speak to your Private Client Adviser for specific information on the role that ETFs may play in managing your wealth.