© 2024 First Samuel Limited

The Markets

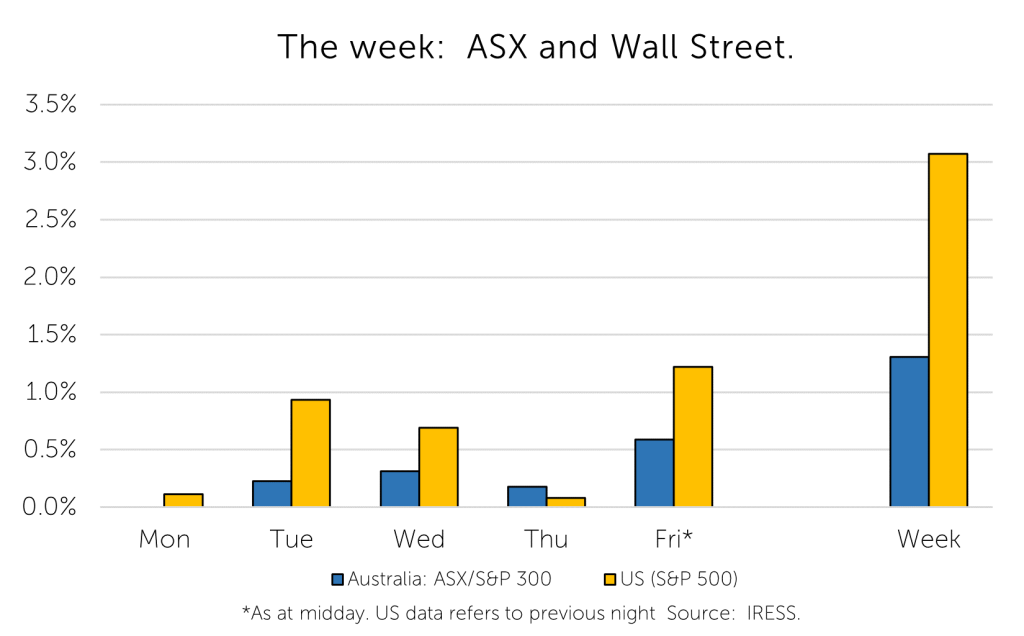

This week: ASX v Wall Street

FYTD: ASX v Wall Street

Labour force opportunities

This week’s Investment Matters strikes out on a different path to usual. We will present background information on the changing nature of the labour force following a decade of rapid aging and massive inbound migration. And the arising investment opportunities.

Investment opportunities

Clients already own positions in Ventia (directly engaged in the themes discussed) and Emeco (partially labour hire).

We are currently researching three more companies that fit this thematic and are being considered for our portfolios.

These changes present investment opportunities that have fallen out of favour with investors and are now trading on single-digit PE multiples, which we consider undemanding. Yet each has a strong market position within its respective industry specialisation.

Demand drivers are changing

Interrupted by Covid and super-charged by policy changes, massive fiscal stimulus and more than two decades of growth in household debt, underlying demand drivers in the economy are changing.

Some of the changes are as expected:

- the aging of the baby boomers is leading to higher demand for health services

- higher levels of workforce participation and greater use of older age cohorts results in growth of externally provided childcare

- higher levels of post-secondary education are lifting the demand for externally provided vocational certification, rather than institutional on-the-job training

Other changes are consistent with changing expectations for the way society is organised, for example:

- The establishment of the NDIS

- Increased demand for HR services

- Regulatory scrutiny extending to otherwise private transactions (e.g. landlord and tenant)

- Diminution in companies’ abilities to take full control over the regulatory and training burden for its workforces

Importantly, the outsourcing and privatisation model of the 1990’s and 2000’s is reaching a natural conclusion

- Even core competencies of local government services now require third party support

- Other transaction with government are often a blend of private and public provision

People’s preferences alter

Together, these policy changes and long-term trends have also been affected by changes in people’s preferences. Consider three in particular:

- Flexibility and movements towards work-life balance, including the flexing of times of work during an ordinary day;

- Active trade-offs made by vast swathes of workers between job conditions, higher pay and greater flexibility; and finally

- Higher real wages sustained over a prolonged period up to the mid 2010’s has seen many workers adopt a preference for part-time work.

The increased complexity of roles, and higher demands by workers for a range of non-pay related conditions of employment, have increased the role for companies that can better manage this more complicated supply chain of workers.

In some cases, these new firms have been created to simply organise staff with particular requirements for the type of work. This allows nurses and health care professionals, for instance, to work in casual roles across a range of hospitals.

In other cases, such as the listed WA-based Mader Group, firms have organised around a particular skill set. In this case the skill set is diesel mechanics; to produce a service for both miners and mechanics.

Mader Group has consolidated the provision of maintenance professional allowing workers access to a range of mine sites, to incorporate flexible training and to allow staff to access a range of services.

The rise of employment service providers

The changing nature of work will affect all companies in different ways.

Consider a large company such as Woolworths, which devotes significant resources to its internal human resource (HR) and recruitment functions.

However, despite doing most of this work themselves, even Woolworths will work closely with external employment services providers for a range of its pathway programs.

A range of government-sponsored, and fully private enterprises have emerged to provide these services to other companies that do not have the resources, the scale or the mandate for such activities.

New service providers are also opportunities for investment

The businesses that have emerged to provide such services have three ways of generating revenue and profits.

The first and simplest is to charge a contracting fee that is a percentage (typically 12% to 25%) of the wage.

The second way is through an increasingly complex, but vast array of government programmes that pay service providers for placing certain types of people, or certain types of skills within particular industries.

The third avenue is to combine a range of services across industries and funding sources.

What new firms have emerged?

Thiess Mining, the world’s largest mining services provider with more than 85 years of mining history, is an example where a company provides the entire workforce and operation as an outsourced solution provider. There are a number of others, including in part Emeco, that provides some services complete with labour and capital equipment.

Companies such as Ventia Ltd, owned by our clients, is an example of a firm committed to providing a trained workforce across a range of infrastructure and community services sectors.

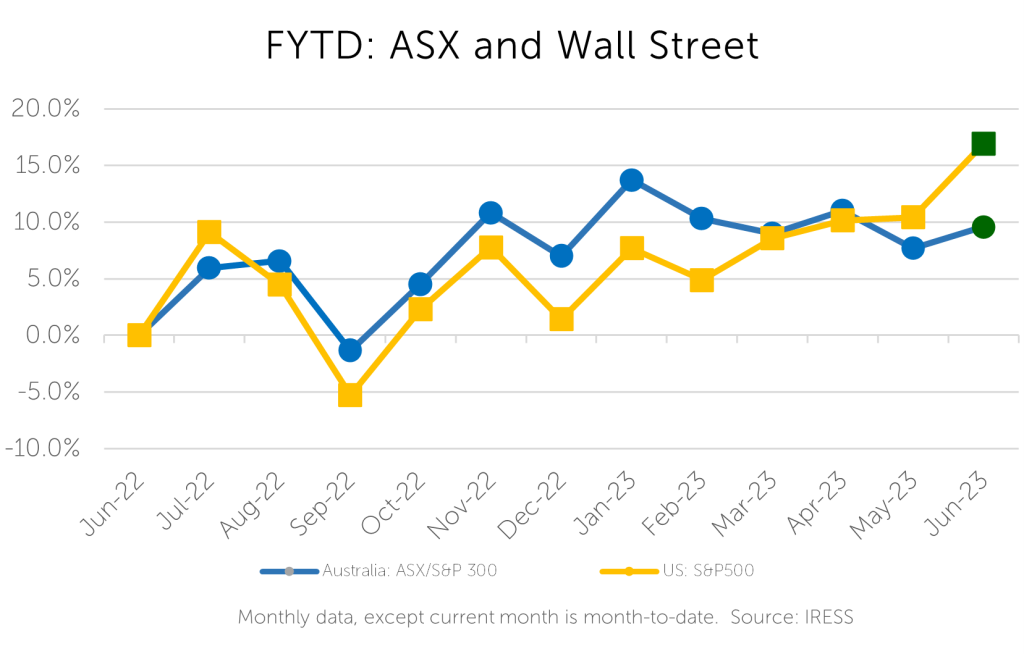

Figure 1 below shows the ramp-up in people related infrastructure, a key growth driver of the types of services that firms such as Ventia provide.

Figure 1: People Intensive Infrastructure Spend

Source: ABS, Melbourne Institute, Minack Advisors

The new workforce organisation model can be especially productive where the training, support and capital augmentation required at the coal face is changing constantly.

The NBN for instance may be better served by employing a firm that can guarantee correctly trained, appropriately tooled technicians, rather than having to train its own workforce.

A composite model for many government-funded sectors

Even in heavily government-oriented businesses, there remains critical components that are outsourced – a composite model so to speak. There are three obvious examples:

- hospitals become increasingly reliant on an outsourced but small fraction of its staff

- childcare operators that outsource casual staffing

- schools that rely on a private workforce of replacement support staff

When the fox runs the henhouse

When changes in the workforce are occurring at the same time as new industries and services are formed, genuinely revolutionary business models are possible.

In Australia in the early 2020’s the gargantuan NDIS roll-out has developed a plethora of new business models. A scarce pool of talent, across a range of health, allied health, administrative and semi-skilled roles, is being deployed in a face of seemingly unlimited public resources.

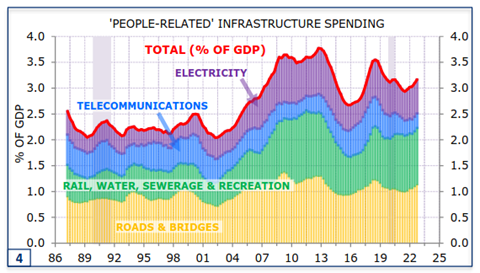

Figure 2: NDIS spending exceeds original estimates

Source: Australian Federal Government

The blowout in the scale and scope of the NDIS, has only been matched, in our view, by the scope for businesses, a number of which are listed, that have been able to quickly capture the outsourcing opportunity.

The NDIS, which is ostensibly a voucher system, has developed into one in which the same firms that organise the decisions around those services for which NIDS recipients are funded also provide the businesses that implement the services.

But this isn’t really a political problem alone, it is directly related to the theme previously discussed. An NDIS would always have to rely on labour organising firms, in the same way hospitals and local governments build a dependency on similar arrangements.

Massive immigration means more than minerals and mining

Our massive immigration programmes have provided more fuel to the growth of the role of these types of firms. Why?

There is considerable complexity in organising newly arrived workers and working holiday makers that would like to use their skills in a range of Australian cities. Consider nurses on working holiday visas that are looking for different roles in different cities.

The complexity of work rules alone often necessitates additional oversight that sole operators would find difficult to manage. Hence the value of a workforce provider than can solve the regulatory issues along with supply of hard-to-get workers, ends up being worth the premium they charge.

How big is this change and the size of the opportunity?

There is one simple figure to illustrate the vast scope of this change: 25%.

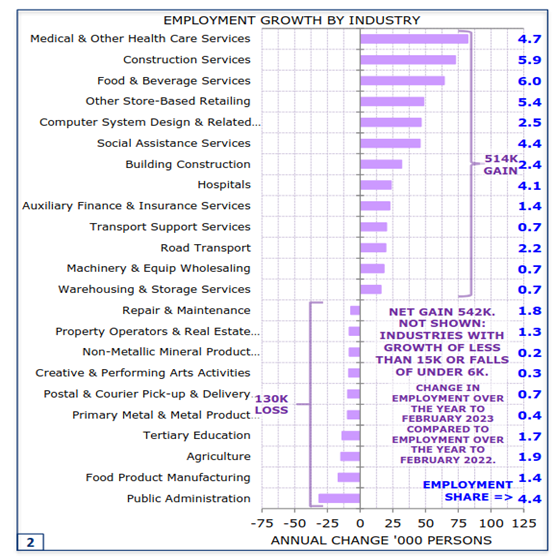

Figure 3 shows the growth in employment in the 12 months to February 2023. Our economy added 542,000 positions. Of these, Medical & Other Heath Care Services added more than 75,000 positions and the closely related Social Assistance Services sub-group added almost 50,000 positions.

Together, more than 25% of new jobs were related to the health trends discussed.

Figure 3: Employment Growth by Industry

Source: ABS Labour Force Survey, Minack Advisors

Health Services employment in Australia – a snapshot

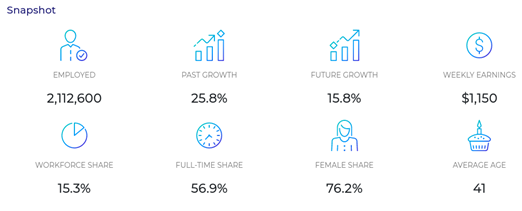

Using the latest data (Figure 4) we can see that more than 2 million people are employed in this sector of the economy. That level has grown by 25% over the past 5 years and has doubled in less than twenty years.

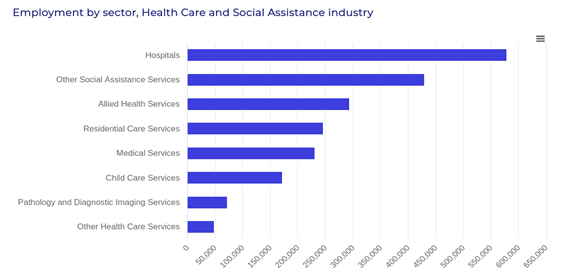

Although Hospitals (Figure 5) remain the largest sub-sector of employment, other social assistance, which will include a large part of the NDIS has now rocketed to be the second biggest sub-sector ahead of Allied Health.

Jobs in the sector are predominantly held by women, and the pay is only moderate (significantly short of males average full-time weekly earnings).

The role of part-time work is clear in the full-time share at levels of only 57%.

Firms designed to managed these workforces are clearly critical in this industry.

Figure 4: Health Services: A fast and future growth area

Figure 5: Employment by sector in HealthCare and Social Assistance

Source: ABS, Labour Force Survey, Detailed, February 2023, seasonally adjusted

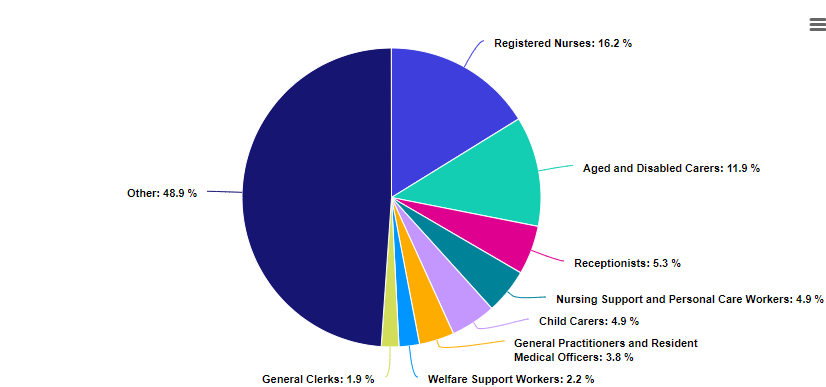

The breadth of roles with the Health Services industry is also worth considering (see Figure 6). In fact, barely half of those employed can be categorised by skill as being the types of roles generally associated with health services.

This breadth makes fertile ground for those who profit from bureaucratic complexity

Figure 6: Employment by role in HealthCare and Social Assistance

Source: National Skills Commission

Implications for wages and economic growth

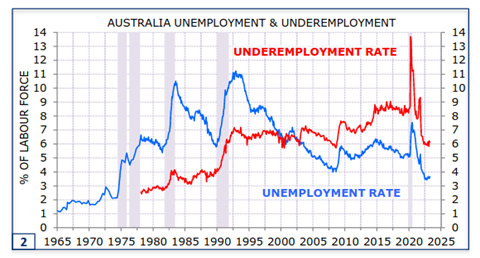

Finally, the vast growth in a narrow range of sectors discussed in the previous section is partly responsible for the low levels of unemployment we continue to see in the economy.

In recent years, and shown below in Figure 8, the level of underemployment is also much lower than in the past 25 years. Under employment began to be a problem in our economy with the de-unionisation and casualisation of the workforce leading up to and following the 1990’s recession.

Many workers were part-time but didn’t want to be, they wanted more hours, and hence were considered underemployed. But for the past 5+ years this level has also fallen, as we would argue the range of flexible alternative, and alternative providers has continued to rise.

Put simply, there are many options of employment and not just as an Uber or food delivery driver.

Figure 7: Declining levels of Unemployment and Underemployment

Source: ABS, Minack Advisors

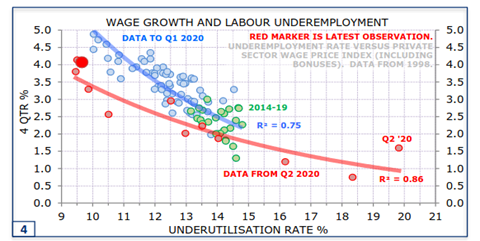

The impact of lower unemployment and under employment over and above the unequivocally positive social benefits will be increasing pressure on wages.

Figure 8: Wage growth and Underemployment – are correlated

Source: ABS, Minack Advisors

The information in this article is of a general nature and does not take into consideration your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any of this information, you should consider whether it is appropriate for your personal circumstances and seek personal financial advice.