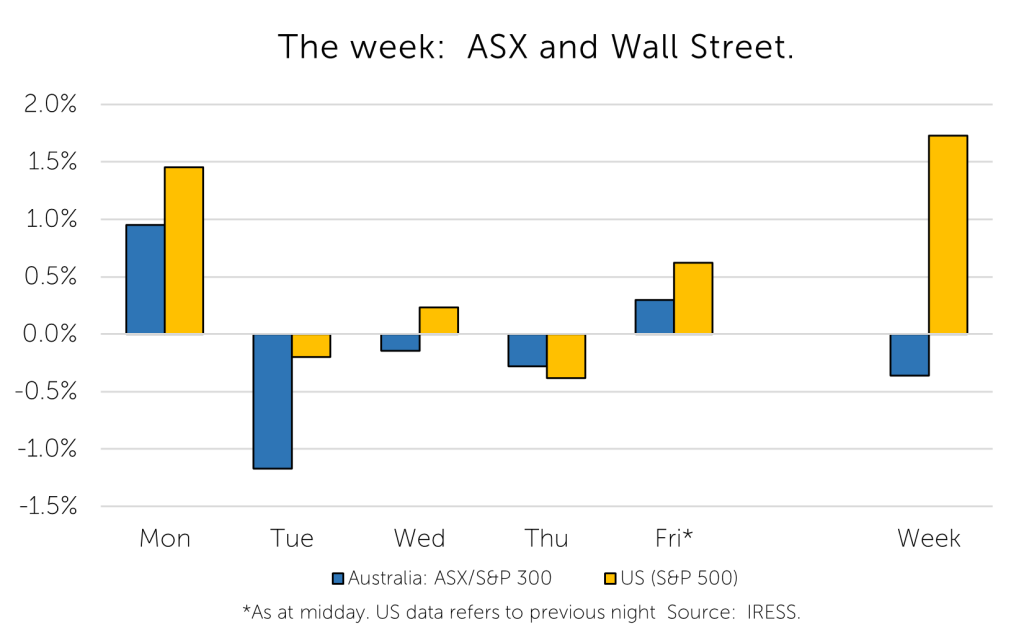

The Markets

This week: ASX v Wall Street

FYTD: ASX v Wall Street

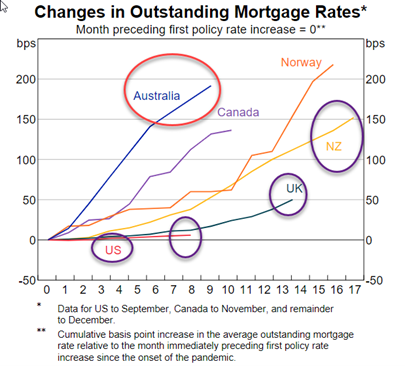

This week’s Investment Matters continues our examination of the RBA’s tightening cycle and the increasing fragility amongst cohorts of Australian consumers. Have the screws been tightened too far already?

We think that the Australian consumer is already showing less resilience than the US consumer, where the interest rate tightening cycle implemented by the Fed has already been put on pause.

But can inflation be curbed in Australia and an economic recession be avoided?

RBA hikes the cash rate again; just necessary or just not listening?

We (and many mortgage holders) were disappointed with the statement that accompanied the Reserve Bank’s 12th rate rise since May last year. If the rise was bad enough already the outlook statement suggests that further rises may be required, and that RBA concerns about inflation and wages growth have increased further.

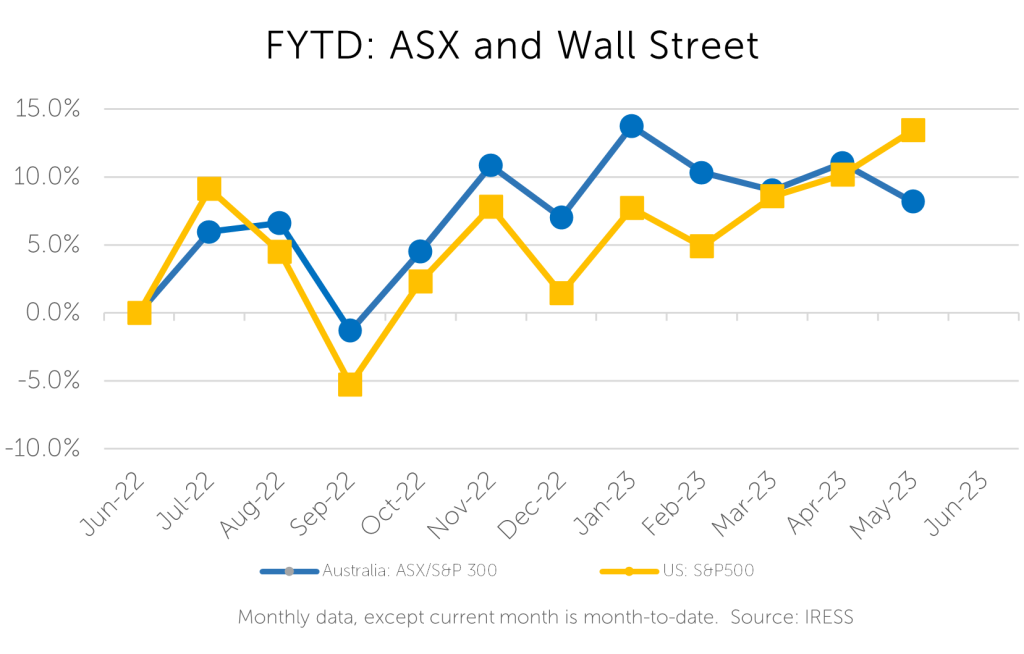

Most market economists believe, as we do, that the impact of previous rises will be hard enough. The inability of our economy to generate the strong wages growth that the RBA always assumes, (and consistently overestimates – see figure 1 below), shouldn’t drive real world outcomes for a small cohort of the economy (notably younger indebted households).

Figure 1– the RBA always exaggerates future wages growth – it should not rely on it when impacting real households

Source: RBA, Minack Advisors

At a point in the cycle when productivity growth is already muted, and investment decisions of firms are looking tepid, we don’t believe that supersonic inflation is the most pressing issue.

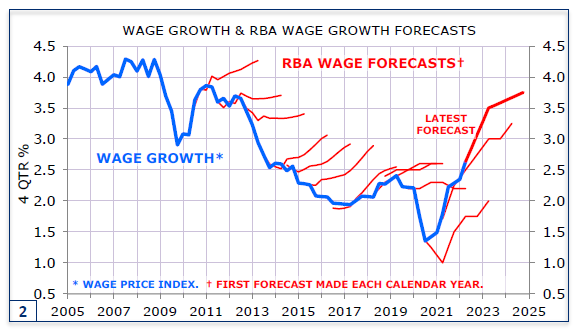

Even if the RBA’s destination for higher rates is validated in coming years, we would suggest it was achieved far too quickly to have been prudent. Australian mortgage interest rates have risen the fastest in the world!

Figure 2 below was produced by the APRA (Australia’s banking prudential regulator) and reproduced in the RBA Bulletin documentation.

Figure 2 – Changes in Outstanding Mortgage Rates – Steeper and larger increases in Australia

Source: APRA, Central Banks, RBA

It tells a story of an Australian mortgage customer/consumer that has been impacted more severely by increases in mortgage rates than other western economies with large stocks of household debt.

This influence has been driven by two factors.

- Given the predominantly variable/floating rate nature of the Australian mortgage market (typically ~80% of mortgages outstanding), the transmission of monetary policy changes (via the RBA cash rate) is usually quite quick.

- The oligopolistic market structure of the Australian banking system is also ‘efficient’ in passing on changes in official cash rates through to mortgage pricing.

But, given the magnitude of cash rate increases (400bps since middle 2022) there is a significant hit to household cashflows coming for those fixed rate borrowers who took out finance in 2021.

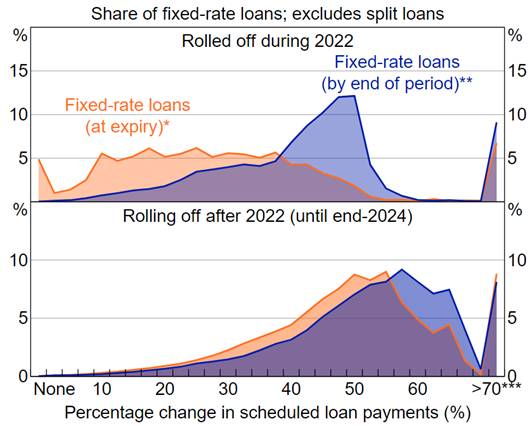

Figure 3: Estimated 50-60% increase in scheduled repayments for maturing fixed rate loans

This is now estimated to translate to up to a 60%+ uplift in mortgage payments for many of those customers as they refinance. Since this chart was created, RBA cash rates have increased further, which will exacerbate this problem.

We think that while typically mid to higher income households would be much more resilient to central bank policy movements, there is an increasing vulnerability of Australian mortgage customers to rising rates. The second half of calendar 2023 looms as a severe test of this contention.

Perhaps the RBA needs to exhibit a bit more patience when lifting interest rates?

Mr and Mrs Consumer – What say you?

Consumption represents more than 50% of the composition of Australia’s GDP. Whilst not as large a share of the economy or the share market as in the US and Europe, consumer behaviour is still a vital component of Australia’s economic health and prosperity. Not all consumers are equal or have the same spending ‘voice’ of course. This leads to disparate impacts across the ASX-listed universe and becomes a consideration for our stock selection in client portfolios.

In this month’s CIO video (issued on Wednesday) and in recent Investment Matters we have noted listed companies such as Universal Store have begun to report on deteriorating conditions. The common feedback including Universal Stores, Adair’s and City Chic reported consumers ‘applying the brakes’ on their spending since Easter/April.

This week it was the turn of Baby Bunting (BBX), which sells clothing and equipment for younger families.

To assist readers to understand this background we dive into the Commonwealth Bank’s ‘Cost of Living Report, March 2023,’ whichprovides useful insights from the spending habits of customers banking with Australia’s largest retail bank.

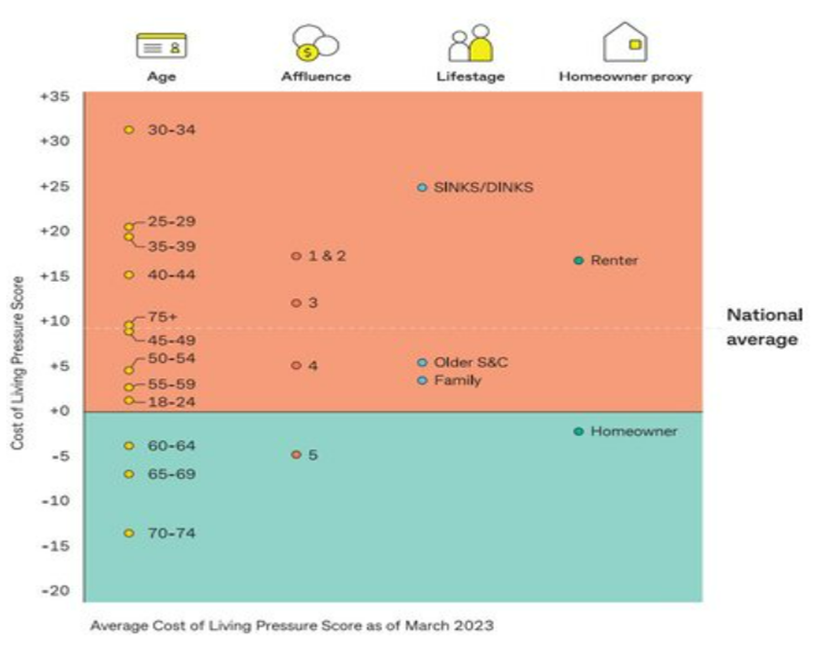

We felt that this schematic, presented below was especially interesting, providing a fantastic short-hand way to represent where cost of living pressures appears to be having most impact upon consumer spending.

Figure 4: Cost of living pressure scores by cohort

Source: CBA iQ, Cost of Living report 2023

In short, the most vulnerability to cost of living pressures is coming from the following cohorts

- 25-35 years of age

- Singles and Couples without children

- Lower to middle income earners

- Renters as opposed to home-owners

Essentials vs Discretionary?

Amongst what might be considered typically more ‘essential’ spending, petrol is where consumers are electing to noticeably ration.

Spending in supermarkets and on insurance is reflecting the inflationary impacts of pricing power within industries with heavy market ownership concentration. It also reflects the benefit of strong immigration, with (discounted) health insurance being a mandatory spend for new arrivals.

Within more discretionary spending categories, travel remains a strong priority for people after a hiatus during Covid. By contrast, it is household goods and apparel spending under most strain.

Younger versus older consumers?

But even between age cohorts, there is significant discretion being applied.

‘Socialising’ and ‘Dining out’ remain popular, even for younger Australians, but new spending on clothing and personal services like hair and beauty services is being wound back.

Figure 5 : Category spend varies sharply by age

| Item | Under 35s | Over 35s |

| Apparel (e.g. clothing, shoes, accessories) | -8.4% | 3.1% |

| Eating Out (e.g. cafes, restaurants, takeaway) | 7.1% | 18.0% |

| Retail Services (e.g. hair, beauty, optometry) | -0.6% | 9.7% |

Source: CBA iQ, Cost of Living report 2023

Given this context, older and wealthier consumers are spending more, and younger and more indebted households are already cutting spending. It follows that the RBA rate rises simply risk exacerbating a vast gulf in economic outcomes.

The economy will slow but the pain will be worn by a narrow range of households despite another cohort (older Australians) having received all the spoils of the past 3 years.

In a battle that we believe should have remained in the textbooks the RBA is fighting a war on inflation because as it notes in this month’s statement

“High inflation makes life difficult for people and damages the functioning of the economy. It erodes the value of savings, hurts family budgets, makes it harder for businesses to plan and invest, and worsens income inequality.”

We could agree. However, what is clear is that in an economy with high mortgage debt concentration, the impact of using higher rates to solve inflation is already increasing inequality.

The information in this article is of a general nature and does not take into consideration your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any of this information, you should consider whether it is appropriate for your personal circumstances and seek personal financial advice.