© 2024 First Samuel Limited

The Markets

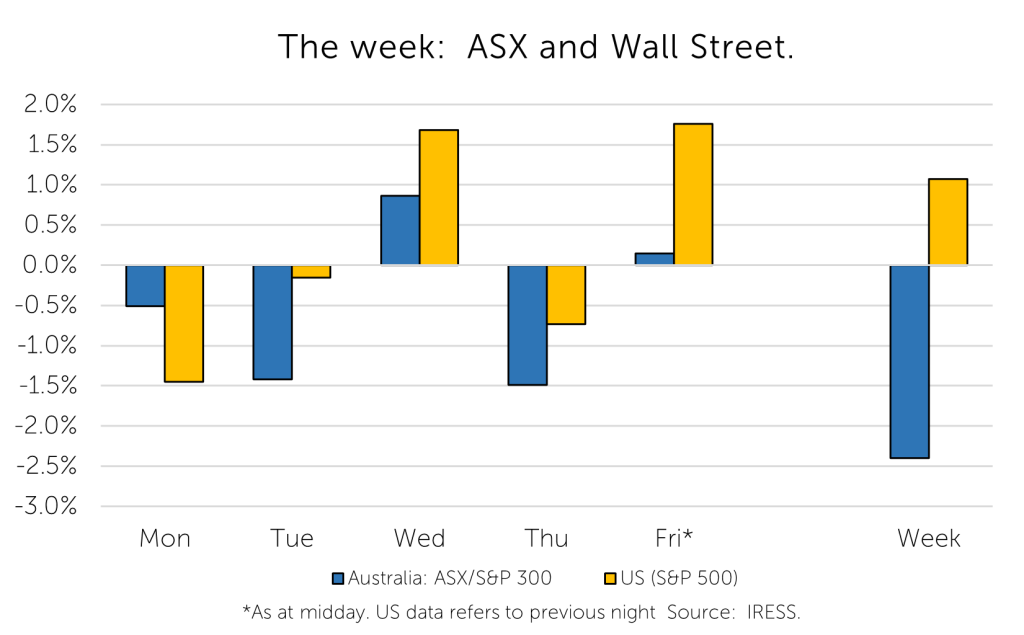

This week: ASX v Wall Street

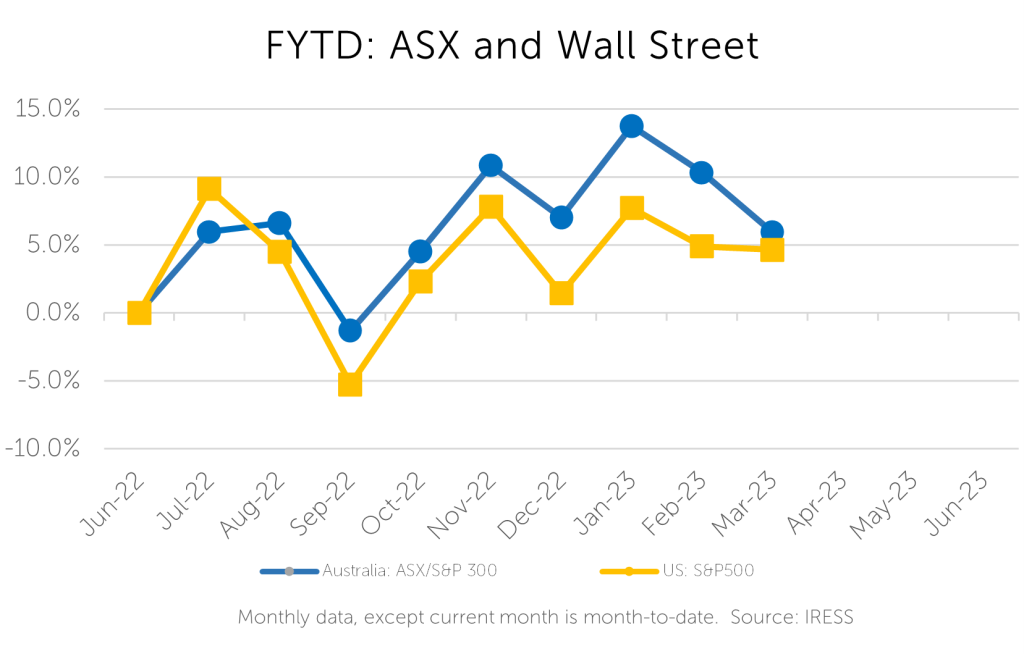

FYTD: ASX v Wall Street

Portfolio action

We used equity market weakness, associated with fears of contagion in the financial system given the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) (and to a lesser extent smaller crypto-focused Signature Bank) in the US, to add to positions in the Australian Bank sector this week.

Until Tuesday trading, the US market (S&P500) had fallen for 5 consecutive days of trading, with investors nervous about the fallout from the impact of rising interest rates and risks in bank balance sheets. Subsequent nervousness and required support for Credit Suisse (Switzerland) and First Republic Bank (USA) have also caused markets to be jittery in the past week.

While Silicon Valley Bank was the second largest registered bank (as measured by assets) to have ever failed in the US (behind Washington Mutual which fell victim to liquidity issues in the Global Financial Crisis of 2008), we believe there are several reasons to feel more comfortable adding to Australian Bank exposures at discounted prices.

With exposures to ANZ, NAB and Macquarie Group, typical client portfolios remain significantly less exposed to bank stocks than ASX300 index.

What was Silicon Valley Bank?

SVB was the 16th largest bank in the US by asset size. Headquartered in California, SVB was a commercial bank that focussed primarily upon meeting the banking needs of technology companies and their executives. Despite its relatively large size, SVB was not a particularly complex or intertwined part of the US financial system.

It was less integrated than entities like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, which were US domiciled broker-dealers (think investment banks) that were integral to the broad extent of problems seen in the GFC.

Why has SVB failed?

As with most bank failures, the primary problem relates to (il)liquidity, in turn caused by asset quality/value concerns.

As at Q4 2022, SVB had the following

SVB was hit by an old-fashioned bank run, with a mass exodus of deposit holders withdrawing funds for fear of bank solvency.

Solvency concerns centred on the quality of the bank’s asset base. Given SVB had more client deposits than loans, excess client deposits were invested in income-generating fixed income assets.

However, given the rapid rise in interest rates and the consequential decline in value of these fixed income securities, the viability of the bank and therefore safety of customer deposits came into question.

No bank in the world keeps sufficient cash on hand to meet the needs of a stampede of deposit holders requesting their deposits/cash all at once. By their nature, banks take customer deposits and use that money to extend credit to those customers who need to borrow.

Should a large number of customers withdraw their deposits all at once, banks will use available cash on hand (only very small amounts), and then will need to start selling more liquid assets (e.g. high quality, short dated bond holdings in Government and other banks commercial paper) to free up money to meet deposit withdrawals. Deposits extended to create customer lending, cannot easily be retrieved, of course!

In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, its typical clientele, being technology company staff and corporates, have been more inter-connected by reason of their industry concentration and electronic communication sources such as Twitter. Word of perceived bank failure spread quickly and the rush on deposit withdrawals happened faster than has been the case historically. For SVB, a massive $42 billion of customer deposits was withdrawn in a single day, last Thursday.

By contrast, Washington Mutual, the largest US bank collapse by asset size experienced a $16.7 billion of customer deposits in a period spanning 10 days before it became illiquid and failed in 2008.

It’s not just good news which travels fast!

4 reasons to feel optimistic about buying Australian Bank shares in response

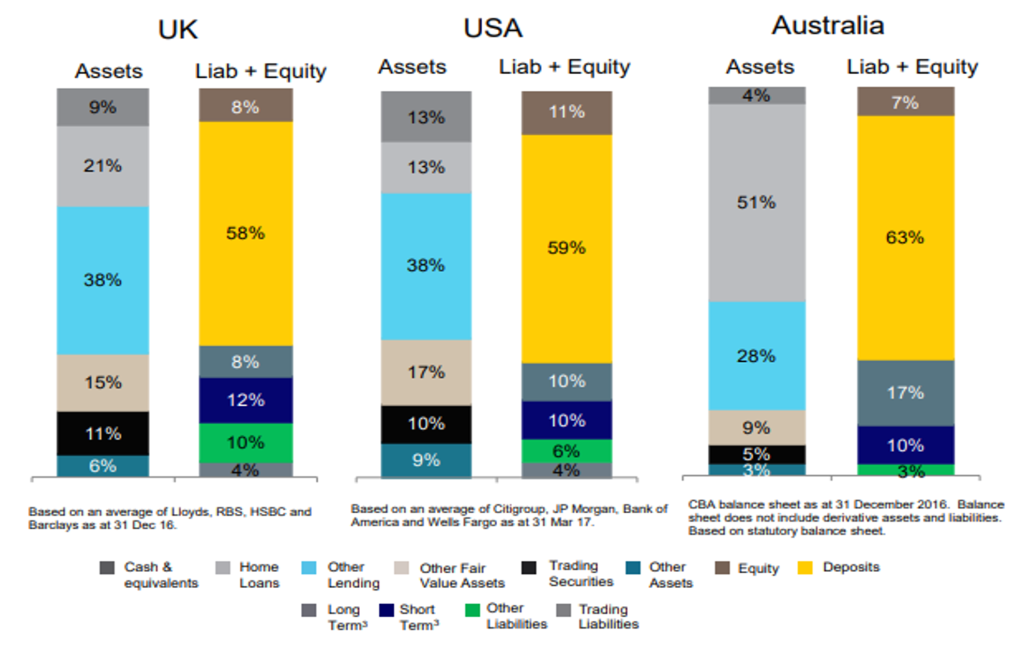

We think there are distinct differences between Australian banks (see CBA data below) and their US peers. This gives us comfort, that a run on a US banking institution like SVB should not be reflected in panic by Australian bank customers nor equity investors.

1/ Asset mix difference

Source: CBA

While this data is a little old (and the structure of bank balance sheets is now even more conservative), Australian banks have typically had a much higher proportion of stable/longer term home loan assets on their balance sheets than their US and UK peers.

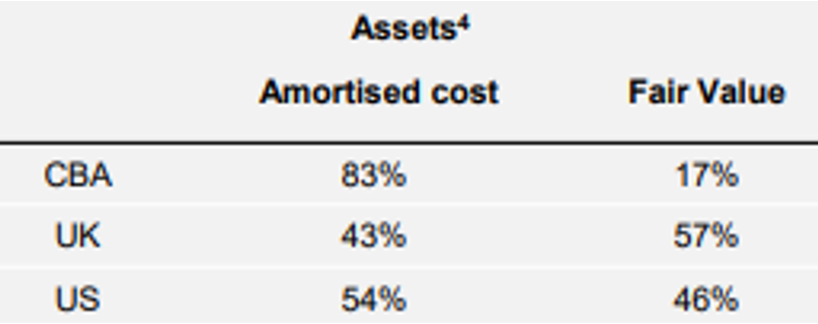

Additionally, they also have a much lower portion of assets held at fair value on their balance sheet, which has been the cause of concern about SVB’s balance sheet.

Source: CBA

2/ Funding/Liability mix is different too

Australian banks have a higher portion of term (>12 months) wholesale funding on their balance sheet.

While it was only relatively recently with the advent of the GFC that saw the introduction of a Financial Claims (Deposit Protection) Scheme being introduced in Australia (on deposits under $250,000 per account holder, per bank), this covers a significant portion of deposit holders in Australian retail banks.

By contrast, only about 4% of SVB’s deposit customers were subject to protection under the equivalent US scheme, increasing anxiety about the safety of customer money.

3/ Australian Banks are more strongly regulated – one national regulator across the sector

US Banks are prudential regulated by one of three broad sets of regulators

- Federal Reserve Board for Bank Holding Companies

- Comptroller of the Currency for national operating banks

- State-based regulators such as the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation which was responsible for regulating SVB

In Australia, banks have a single prudential regulator, APRA, which is able to take an industry-wide view, compare and contrast the individual bank’s balance sheets and behaviour and, if necessary, call them to account.

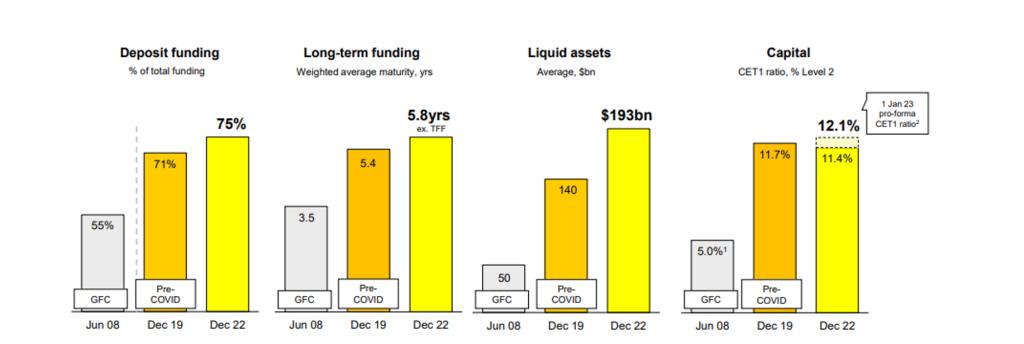

4/ Strengthened balance sheets post GFC – equity, liquidity, longer duration funding

Australian banks have demonstrably improved the resilience of their balance sheets, holding higher levels of equity, extending the term of their wholesale funding and holding more liquid assets.

Source: CBA

Conclusion

In summary, we see clear differentiation between the mismanagement of the balance sheet that has been apparent at Silicon Valley Bank and the contrasting solidification of Australia’s largest banks’ balance sheets.

While we remain underweight Australian banks in an Australian market context, we’ll look for opportunities to add to weightings in the event that their share prices are negatively impacted by news flow pertaining to offshore bank failures.

The information in this article is of a general nature and does not take into consideration your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any of this information, you should consider whether it is appropriate for your personal circumstances and seek personal financial advice.